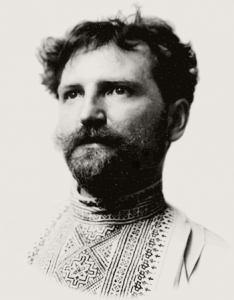

Alphonse Maria Mucha was born in the town of Ivančice, Moravia, today's Czech Republic, on 24 July 1860.

Excited by light and colour, Mucha's earliest memory was of Christmas tree lighting.

His singing skills enabled him to continue his education through secondary school in the Moravian capital Brünn (now Brno), although drawing was his first love since childhood.

A baroque fresco in his local church awakened his interest in art, and he began working as a decorative painter in Moravia.

Mostly painting theatrical sets, he moved to Vienna in 1879, where he became an apprentice stage painter. Surrounded by the explosion of art in the Austrian capital, he learned and admired the work of Hans Makart. He worked for a leading Viennese theatre design company, while informally continuing his artistic education. When a fire destroyed his employer's business in 1881, he returned to Moravia, where he did freelance decorative and portrait painting. Mucha grew up in the shadow of two powerful cultural forces: the Catholic Church and the Slavs' desire for independence from the Austrian Empire.

To earn his living, he carried out portrait commissions. This led him to an important mentor, Count Khuen-Belasi, who hired him to paint murals in Hrusovany-Emmahof Castle.

Mucha's own poverty and popularity were brought into sharp focus while he worked at the castle. His poverty was so great that his only real trousers became so shabby that a group of community girls bought him new ones.

Count Khuen-Belasi paid for Mucha's training in fine art in Munich, where he continued to work as an illustrator, notably for the magazine Krokodil, where he developed his distinctive calligraphic style.

In 1887 he was in Paris and studied at the Académie Julian and Académie Colarossi. Here, artists such as Vuillard and Bonnard came to the fore.

Along with these artists came new ideas about what art could do. Art was seen as an endeavour that could reveal greater mysteries, and as something to be incorporated into everyday life and objects. These ideas began to develop into what would become the Art Nouveau conception of art in everyday life.

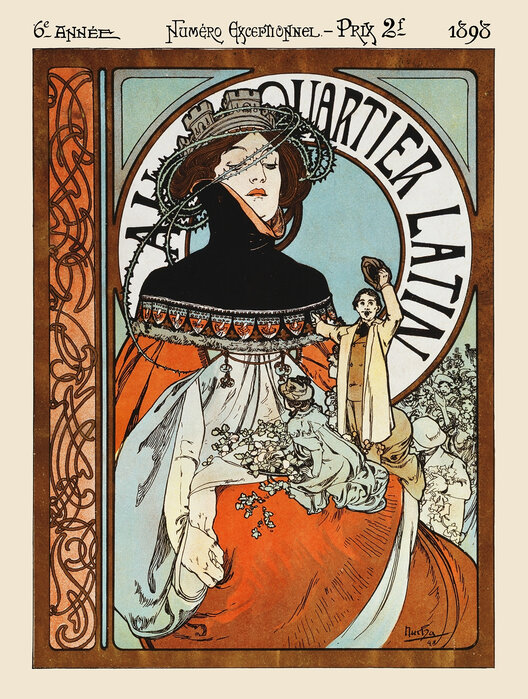

It was an overnight sensation and announced the new artistic style and its creator to the citizens of Paris. Bernhardt was so pleased with the success of that first poster that she entered into a six-year contract with Mucha.

Mucha produced a flood of paintings, posters, advertisements and book illustrations, as well as designs for jewellery, carpets, wallpaper and theatre sets in what was initially called the Mucha style, but became known as Art Nouveau, French for 'new art'. Mucha's works often featured beautiful healthy young women in flowing, vaguely neoclassical-looking robes, often surrounded by lush flowers that sometimes formed halos behind the women's heads. In contrast to contemporary poster artists, he used lighter pastel colours.

The 1900 World Fair in Paris spread the "Mucha style" internationally, of which Mucha said, "I think [the Exposition Universelle] has made some contribution to bringing aesthetic values to art and crafts." He decorated the Bosnia and Herzegovina Pavilion and collaborated on the Austrian Pavilion. His Art Nouveau style was often imitated.

However, this was a style Mucha tried to distance himself from throughout his life; he always insisted that, rather than sticking to a fashionable stylistic form, his paintings came purely from within and Czech art. He declared that art existed only to convey a spiritual message, and nothing more; hence his frustration with the fame he gained from commercial art, when he always wanted to concentrate on more elevated projects that would elevate art and his birthplace.

In 1910, despite his enormous success in Paris, Mucha returned to the Czech Republic. He devoted the rest of his life to a series of monumental works about the history of the Slavic people, the Czechs in particular. He hoped to rekindle a nationalistic consciousness after years of oppression by the Austro-Hungarian empire. The American Charles Crane sponsored the work. Mucha himself considered this series to be his most important work.

It expressed his patriotic feelings and his support of Panslavism. For these twenty works he made several study trips through Eastern Europe.

Mucha worked for eighteen years on the paintings that depict the most important events in Slavonic history. The works are divided along four lines: allegory, religion, battles and culture. The main themes are the celebration of the Slavic people, the liberation from foreign powers and Slavic unity. In 1919, the first 11 works were exhibited in the Clementinum in Prague. They were only moderately received. In 1928 Mucha donated the entire epic to the city of Prague. In 1935 the canvases were rolled up and during the Second World War and the following communist regime they were forgotten.

By the time of his death, Mucha's style was considered outdated. However, his son, author Jiri Mucha, devoted much of his life to writing about him and bringing his art to the attention of the public. Interest in Mucha's distinctive style had a strong revival in the 1960s (with a general interest in Art Nouveau) and was particularly evident in the psychedelic posters of Hapshash and the Colored Coat, the collective name for two British artists, Michael English and Nigel Waymouth, who designed posters for groups such as Pink Floyd and The Incredible String Band. In his own country, the new authorities were not interested in Mucha.

Only in 1963 were the canvases exhibited again at the castle in Moravsky Krumlov in Mucha's native Moravia. At the end of July 2010 the exhibition was closed. The works were transferred to Prague, although Mucha's family opposed this.

His Slavonic Epic was rolled up and stored for twenty-five years before it was shown in Moravsky Krumlov and only recently has a Mucha Museum in Prague, run by his grandson, John Mucha.

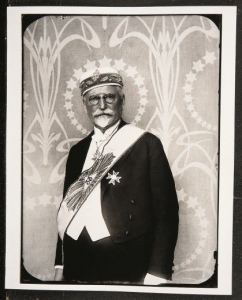

Mucha the Freemason.

Mucha joined a lodge in Paris in 1898 and after returning to Prague he helped found the first Czech speaking lodge, Jan Amos Komenský.

In 1923 Mucha became Grand Master of the new Grand Lodge of Czechoslovakia and in 1930 he was elected Sovereign Grand Commander of the High Council in the AASR or Ancient & Accepted Scottish Rite of Czechoslovakia.

He designed famous lapels and jewellery for the Czech Grand Lodge, with his unique style. After Freemasonry was banned by the Nazis during the Second World War, it resurfaced and today the brotherhood is led by the Grand Lodge of the Czech Republic.

As an artist, Mucha made a great contribution to the artistic representation of various artifacts of Czechoslovak freemasonry. He was the author of graphic magazines and designed Masonic stationery and stamps.

Mucha's designs of Masonic jewellery are also very popular worldwide.

His close association with Freemasonry made him a target for the Gestapo when the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939. They caused massive damage in Bohemia and Moravia, with the explicit order to completely exterminate the Slavs and Jews there. Hitler had declared that both peoples were "subhuman". As Freemasons were considered servants of Judaism, Freemasons were also directly targeted. Mucha's importance within the Czech Grand Lodge made him a valuable prize. Betrayed by an associate named Arved Smichkovsky, he was arrested at the age of 79 and subjected to harsh interrogations by the Gestapo.

Soon he was diagnosed with pneumonia and released in a weak condition.

Mucha died on 14 July 1939. In open defiance of the Nazi ban on public gatherings, more than 100,000 Czechs attended his funeral and he was praised in speeches by his fellow anti-fascists.

-

Thierry Stravers is co-owner of Masonic Store.

He likes to combine his passion for style and elegance with his Masonic activities.

Thierry is the owner of Trenicaa marketing agency and is a board member of Loge Enlightenment No.313 O: Hoofddorp.